The priorities in the treatment of retinoblastoma are in order of preservation of life, eye, and then vision. Close teamwork between a multidisciplinary team comprising of the ophthalmologist, paediatric oncologist, geneticist, interventional radiologist and pathologist is essential to achieving those goals. At present, the goal of preventing mortality has largely been met, and retinoblastoma is now the most curable paediatric cancer.

Staging the Disease

To determine the most suitable treatment, a thorough evaluation to stage the disease has to be performed first. In young children, they are generally unable to cooperate with the eye examination when they are awake. As such, they are usually examined under sedation or anaesthesia. The pupils are dilated so the entire retina can be thoroughly examined to determine whether there is one or more retinoblastoma is present. The examining doctor will also assess for seeding into the vitreous or front chamber of the eye.

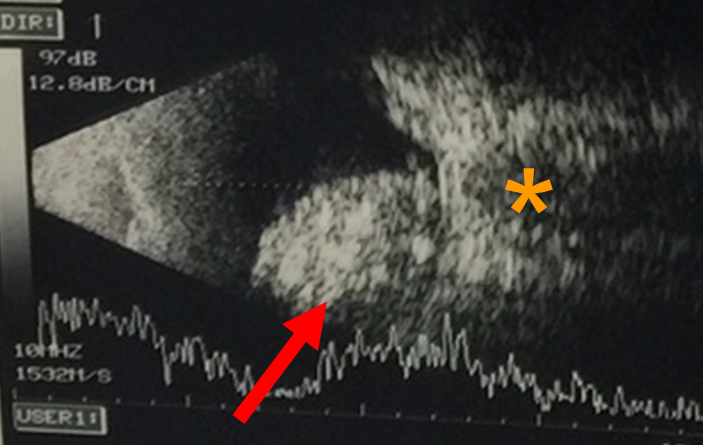

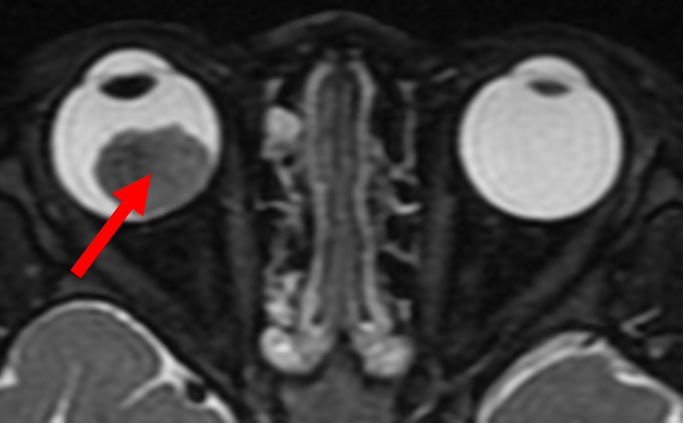

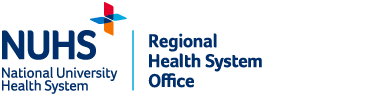

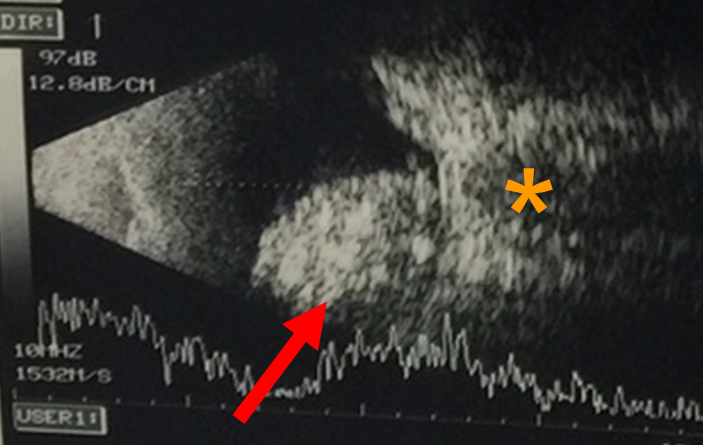

An ultrasound of the eye (Figure 2) is performed to evaluate for characteristic features for the tumour, such as calcification, and to measure the size of the tumour. To assess for spread of the tumour outside the eye, or into the brain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbit is performed (Figure 3). In both ultrasound and MRIs, there is no exposure to radiation.

Figure 2 - This is an ultrasound scan that demonstrates the tumour (arrow), which is in close proximity to the optic nerve (orange asterisk).

Figure 3 - This is an MRI scan that demonstrates the tumour (red arrow) in the right eye. The MRI is useful to assess for extension of the tumour outside the eye, and intra-cranial involvement of the disease.

Treatment Options

Overall, the need for removal of the eye to treat Retinoblastoma has gone down substantially. Once considered the treatment of first choice, it is now considered only when all other forms of conserving the eye (systemic or intraarterial chemotherapy) have been exhausted or not possible. It is typically indicated in children with advanced cancer in only one eye, especially in older children (above two years of age), when it is rapidly therapeutic and avoids the risks and complications from other forms of treatment.

Note: An eye is usually removed only when absolutely indicated and no longer the treatment of first choice.

Various other treatment modalities are available in the management of a retinoblastoma:

- Photocoagulation or cryotherapy can be used in the treatment of small tumours.

- For medium to large sized tumours with no systemic spread, the treatment has rapidly evolved. Enucleation is an established treatment, but there is complete loss of visual potential in the operated eye. In cases with very advanced unilateral disease and no likelihood of functional vision, this is still the treatment of choice.

- For less severe disease in eyes with vision potential, there are several globe salvage treatments that are available:

Intra-arterial chemotherapy - NUH is the only institution in Singapore and the region to offer Selective Intraarterial Chemotherapy for Retinoblastoma, performed by our neurointerventional radiologist. This, complemented with intraocular laser therapy, cryotherapy, intravitreal chemotherapy performed by the Ophthalmologists and systemic chemoreduction offered by our paediatric oncologists makes multimodality multidisciplinary management of Retinoblastoma possible.

This treatment involves super-selective infusion of chemotherapy into the ophthalmic artery, the blood vessel that delivers blood to the eye. This maximises the bioavailability of the drug in the targeted ocular structure, while minimising systemic drug exposure. The current chemotherapeutic regimen used in intraocular chemotherapy comprises single or combined use of these three agents: melphalan (most commonly), topotecan or carboplatin. This treatment modality was first introduced in 2006. A review of patients with advanced group D or E disease, did not find any increase in the chance of orbital recurrence, metastatic disease, or death compared to primary enucleation. This procedure is generally safe but there are some potential side effects. Transient side effects that generally resolve within six months include swelling of the eyelid, drooping of the eyelid, loss of lashes, redness of the skin over the forehead, and temporary limitation in eye movements. More serious potential side effects include occlusion of the retinal artery or vein and choroidal atrophy, which can give rise to visual loss. Systemic side effects also include low white blood cell counts, risk of stroke and allergic reactions.

Intra-vitreal chemotherapy - This involves the injection of the medication directly into the vitreous cavity of the eye, to treat refractory and recurrent seeding of the tumour into the vitreous.

Reported complications include cataract formation, bleeding in the vitreous cavity, retinal haemorrhage and low eye pressures. There is also a risk of introducing infection into the eye which can cause loss of vision.

There is also a theoretical risk that the tumour cells can spread through the needle track.Techniques used to minimise this risk include applying cryotherapy to the injection site before removing the needle, or using distilled water to wash the eye after needle removal, as distilled water has been shown to be effective at killing retinoblastoma cells in culture within a few minutes.

Systemic chemotherapy - Systemic chemotherapy may also enable globe salvage, often times with useful vision, but increases the risk of secondary tumours such as leukaemia, low blood counts, kidney toxicity and hearing loss. However, in patients with metastatic disease, multiple-agent intensive systemic chemotherapy is used to treat tumour cells have disseminated to other parts of the body.

Radiotherapy - In general, this approach has been abandoned because of the subsequent risk of second cancers, and there are other more efficacious treatment options.

Survelliance

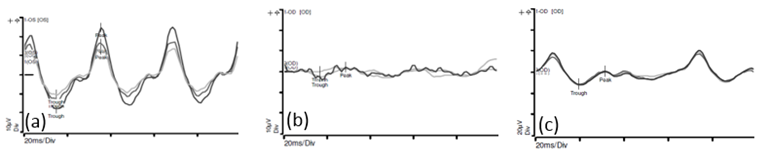

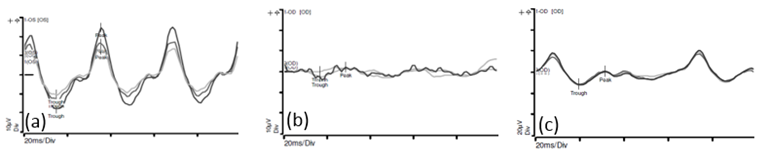

The electroretinogram (ERG) is an objective and noninvasive method for evaluating the visual pathway (Figure 4). An ERG is the recording of electrical signals produced by the retina when stimulated by a brief flash of light. Reduction in the ERG amplitude has been found to be grossly proportional to the degree of retinal disruption or toxicity. In our centre, ERGs are performed prior to each session of intra-arterial chemotherapy to monitor the retina function.

Figure 4 -

(a) This is the recording of the electrical activity in a normal eye

(b) This is the recording of the electrical activity in an eye affected by a retinoblastoma. There is reduced amplitudes and loss of the normal sinusoidal pattern.

(c) This is the recording of the electrical activity of the eye shown in (b), after 2 cycles of intra-arterial chemotherapy. There is improvement in the amplitudes and more semblance to the normal sinusoidal pattern.

Following successful treatment with regression of the tumour, surveillance needs to be continued as there can be recurrence of disease or development of additional eye tumours.